A00400 - Final Notes on Highwarden Just, Amherst College Class of 1940: Margaret Just Butcher, Civil Rights Activist, Educator and Alain Locke Collaborator

In addition to his trailblazing father, Ernest Everett Just, and his impressive code breaking mother, Ethel Highwarden Just, Highwarden Just also had a big sister who herself made history in a number of arenas. Below is the Black Past article on Margaret Just Butcher. You can read for yourself the significant contributions that she made during her long life. However, of special note for the alumni of Amherst College please note that Margaret's first marriage was to a member of a fairly large and prominent Washington, D.C. African American family. From this union, came Margaret's only child, Sheryl Everett Wormley, a last name that she shares with Amherst College's Green Dean from 1972-73.

Margaret Just Butcher (1913-2000)

Margaret Just Butcher

Fair use image

Activist, writer, and educator Margaret Just Butcher was born on April 28, 1913, in Washington, DC, to Dr. Ernest E. Just, the renowned scientist and advisor and incorporator of the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. from Charleston, South Carolina, and Ethel Highwarden, one of the first Black female graduates of Oberlin College from Columbus, Franklin, Ohio. Margaret had one brother, Highwarden Just, and a younger sister, Maribel Just Butler.

Butcher, who was poly-lingual (French, Italian, German, and Arabic), graduated from M Street High School in the District of Columbia in 1930 and received the B.A. degree from The University of Pennsylvania in 1934. She also earned a Ph.D. from Boston University in 1947 and studied at the Université Paris-Sorbonne.

In 1935, Butcher taught English and Literature at Virginia University for one year and then in 1936 married Dr. Stanton L. Wormley, Dean of Men and Acting President of Howard University. They had one daughter, Sheryl Everett, but divorced after one year. She left Richmond to take a teaching position in the District of Columbia Public Schools, remaining there from 1937 to 1941. From 1942 to 1955 she was a Professor of English at Howard University. While there she assisted National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) legal counsel and future U.S. Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall as a special educational consultant. During the summer of 1954 she led demonstrations opposing racial segregation in the District of Columbia.

In 1949 Margaret married James W. Butcher, professor of English and Theater at Howard University and the following year she became a Fulbright visiting professor in the humanities at the Université de Lyon and Université Grenoble Alpe in France.

When Butcher’s godfather, Dr. Alain LeRoy Locke, fell ill, he asked Butcher from his sickbed at Valley Forge Medical Center and Hospital in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania to complete his planned book, The Negro in American Culture. Locke died on June 9, 1954 and with her help, the book was published on January 1, 1957.

Margaret Butcher divorced James Butcher in 1959 before leaving Paris. Shortly afterward she headed the English Language Training Institute in Casablanca, Morocco from 1960 to 1965.

In 1968 with the creation of Federal City College (now the University of the District of Columbia), Butcher was invited to join the faculty. At the same time, however, she was also offered the position of assistant cultural attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Paris, France. She took the position and remained there from 1968 to 1971. In 1971 she returned to the United States and worked at Federal City College as the “Star Professor of English” until her retirement in 1982.

An active member of the Washington DC branch of the NAACP, she also served as a member of the District of Columbia Board of Education from 1953 to 1957, and a member of the National Civil Defense Advisory Council, Margaret Just Butcher, died on February 7, 2000, in Washington, D.C. She was 86.

Margaret Just Butcher

Margaret Just ButcherMargaret Just Butcher (April 28, 1913 – February 7, 2000) was an American educator and civil

During the 1950s, she was a Fulbright Visiting Professor at two universities in France. In the early 1960s she taught in two cities in Morocco, and then served as a cultural affairs attache in Paris, returning to Washington, D.C., in 1968. She taught in its public schools for a time.

Beginning in 1953, Butcher served on the city's Board of Education. She also worked with the NAACP on their suit for desegregation of public schools. Following the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) ruling by the US Supreme Court, she pressed city officials to proceed with desegregating the schools.

Butcher is also known for her collaborative work with philosopher and cultural leader Alain Locke, who had been a mentor at Howard University. They became friends and she helped care for him in his last illness. From his notes and their discussions, she edited and completed The Negro in American Culture, which was published in 1956 after his death.

Early life and education

[edit]Margaret Just was born in Washington, D.C., on April 28, 1913, to educated parents.[2] Her father was biologist Ernest Everett Just, and her mother, Ethel Highwarden, was an educator.[3] She was provided the best schooling in the area and studied in Italy with her father in 1927.[2] She earned her Ph.D. in 1947 from Boston University.[2]

Career

[edit]Educator

[edit]Just worked as a professor of English at Virginia Union during the 1935-1936 school year.[2] She taught public school in Washington, D.C., from 1937 to 1941, when teachers were federal employees.[2] In 1941, she was selected as a Rosenwald Fellow.[4] Starting in 1942, she taught at Howard University, where she became a colleague of professor Alain Locke.[2]

In 1950 Butcher (who had married the previous year) went to Europe as a Fulbright Visiting Professor.[5] She was the first woman to serve as a visiting professor in the Fulbright program.[4] In Europe, she taught at the University of Grenoble and the University of Lyon in France.[6][5] She also worked to interview other Fulbright candidates in France.[5] After her return to Washington, she taught at Howard until 1955.[2]

From 1960 to 1965, Butcher taught overseas again. She taught English and American culture in Rabat and was the director of the English Language Training Institute in Casablanca, Morocco.[7][3] She also worked as the "cultural affairs attache to Paris" in the 1960s, returning to Washington in 1968.[8][9]

After her return to the capital, she taught at Federal City College from 1971 to 1982.[2]

Civil rights work

[edit]Butcher was a passionate advocate for civil rights.[2] In 1953, she was named as a member of the Washington, D.C., Board of Education, replacing Velma G. Williams.[10] The Pittsburgh Courier praised her "militant" approach to fighting segregation in public schools.[11] Butcher found discrepancies between the schools for white and black students and called out the inequity in the classrooms.[12]

From 1954 to 1955, she worked with Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund as a special education consultant for their suit about segregation in schools.[13]

After the Supreme Court ruled that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, Butcher warned there were additional fights against discrimination facing black people in America.[14] The superintendent of the Washington, D.C., schools, Hobart M. Corning, favored a gradual approach to integrating the schools, which Butcher disagreed with.[15] A white nationalist group, the NAAWP, called for her to resign from the board and called her a "'tool' of the NAACP", unable to be objective on school integration.[16]

Butcher was open about her work for the NAACP and publicly criticized Corning's plan to delay integration in Washington schools.[17] She discussed the plans to integrate the schools on behalf of the NAACP at the annual meeting of the Newport News branch in 1954.[18] In 1955, Butcher continued to speak out against gradual integration, saying that the Washington schools were still largely segregated and that waiting would not accomplish their goals.[19] The New York Age called her a "constant thorn in the side of the Washington, D.C., school board."[20] She remained on the board until 1956.[3] During this period, Virginia and other Southern states conducted massive resistance; in some instances, school districts closed rather than achieve any integration. Because private schools were not covered by the Supreme Court's ruling, numerous private religious schools were opened across the South, known as "segregation academies".

The Lambda Kappa Mu sorority honored Butcher for her fight against segregation in 1954.[21]

Politics

[edit]Butcher was appointed in 1952 to the National Civil Defense Advisory Council.[22] She succeeded Mary McLeod Bethune, who retired due to health issues.[23]

In 1956 and 1960, Butcher served as a delegate from the District of Columbia to the Democratic National Convention.[2]

The Negro in American Culture

[edit]Butcher wrote The Negro in American Culture, based on the notes of her mentor and friend, Alain Locke and furthering his work.[24][2][25]

When Locke became sick, Butcher helped care for him, visiting him at home daily, preparing meals for him, and taking him to the hospital.[2][24] After Locke died, Butcher used notes that Locke left for her and finished his work.[26] The book was published in 1956, revised and reprinted in 1971, and translated into 11 different languages.[12]

Personal life

[edit]Butcher was briefly married to Stanton Wormley. They had a daughter, Sheryl Everett Wormley, before they divorced.[2]

Around 1949, Just Wormley married James W. Butcher Jr., a Howard drama professor.[27] In 1959 she sought a divorce from her husband, and kept his name.[28] Her daughter, Everett Wormley, eventually held a "high science post."[12]

Butcher died on February 7, 2000, aged 86, in Washington, D.C.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Fund, Julius Rosenwald (1940). "Review for the Two-year Period".

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m Boyd, Herb (August 22, 2019). "Dr. Margaret Just Butcher, Educator and Political Activist". Amsterdam News. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Barnes, Paula C. (1993). "Butcher, Margaret Just". In Hine, Darlene Clark; Brown, Elsa Barkley; Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn (eds.). Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Brooklyn, New york: Carlson Publishing Inc. pp. 207. ISBN 0926019619.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Margaret Butcher, Capital Teacher Gets Defense Post". Waco Tribune-Herald. August 17, 1952. p. 27. Retrieved February 15, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c "Howard U. Prof. Hailed In Europe". The Pittsburgh Courier. July 22, 1950. p. 6. Retrieved February 14, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Educator to Talk at Central State". The Journal Herald. March 26, 1954. p. 2. Retrieved February 14, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Morocco Teacher to Speak". The Akron Beacon Journal. December 1, 1962. p. 9. Retrieved February 17, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Morch, Albert (August 30, 1974). "Prince Here for Sailing Competition". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 26. Retrieved February 17, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "CLA News". CLA Journal. 12 (2): 178. 1968. ISSN 0007-8549. JSTOR 44321495.

- ^ "Howard U. Prof. On D.C. Board". The Pittsburgh Courier. June 27, 1953. p. 10. Retrieved February 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New D.C. School Board Appointee a Fighter!". The Pittsburgh Courier. January 9, 1954. p. 4. Retrieved February 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Hamilton, Mildred (September 3, 1974). "A Lifelong Opponent of Injustice". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 23. Retrieved February 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Cover: Margaret Just Butcher Biographical Note". Negro History Bulletin. 20 (1): 15. 1956. ISSN 0028-2529. JSTOR 44215203.

- ^ "Negroes' Battle to Be Continued". The Greenville News. April 6, 1954. p. 16. Retrieved February 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "U.S. Capital School Directors Outline Anti-Segregation Policy, But Delay Action". The Morning Call. May 26, 1954. p. 10. Retrieved February 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Rivera, Jr., A. M. (November 6, 1954). "NAAWP Seeking Ouster". The Pittsburgh Courier. p. 13. Retrieved February 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "NAACP Member Criticizes [sic] DC School Superintendent". The Times and Democrat. November 20, 1954. p. 5. Retrieved February 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Professor is Speaker for NAACP Unit". Daily Press. November 7, 1954. p. 33. Retrieved February 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Segregation Remains in D.C. Schools Says Dr. Butcher". The Pittsburgh Courier. January 15, 1955. p. 3. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ Blackwell, Lee (January 8, 1955). "1954 in Review". The New York Age. p. 9. Retrieved February 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dr. Margaret Butcher of D.C. is Honored by Nat'l Sorority". Alabama Tribune. December 3, 1954. p. 4. Retrieved February 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dr. Margaret Just Butcher asso-". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. July 16, 1952. p. 11. Retrieved February 14, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Replaces Mrs. Bethune". The Pittsburgh Courier. June 28, 1952. p. 2. Retrieved February 17, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Boyd, Herb (August 22, 2019). "Dr. Margaret Just Butcher, Educator and Political Activist". New York Amsterdam News. p. 2. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ "Dr. Margaret J. Butcher, Star Professor of Eng-". The Pittsburgh Courier. December 25, 1971. p. 11. Retrieved February 17, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Winslow, Henry F. (December 1956). "Mosaic Vision". The Crisis. 63 (10): 633–634.

- ^ Peterson, Bernard L. (1990). Early Black American Playwrights and Dramatic Writers: A Biographical Directory and Catalog of Plays, Films, and Broadcasting Scripts. New York: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-313-26621-8.

- ^ "Margaret J. Butcher Seeks Divorce from Hubby". Jet. 16 (5): 13. May 28, 1959.

"On June 12, 1912, he married Ethel Highwarden, who taught German at Howard University. They had three children: Margaret, Highwarden, and Maribel. The two divorced in 1939.[6] That same year, Just married Hedwig Schnetzler, who was a philosophy student he met in Berlin.[6]

"In 1940, Just was imprisoned by German Nazis, but was easily released thanks to the help of his wife's father.[6]"

The Black Women Code Breakers of Arlington Hall Station

Their top-secret unit played a critical role during World War II.

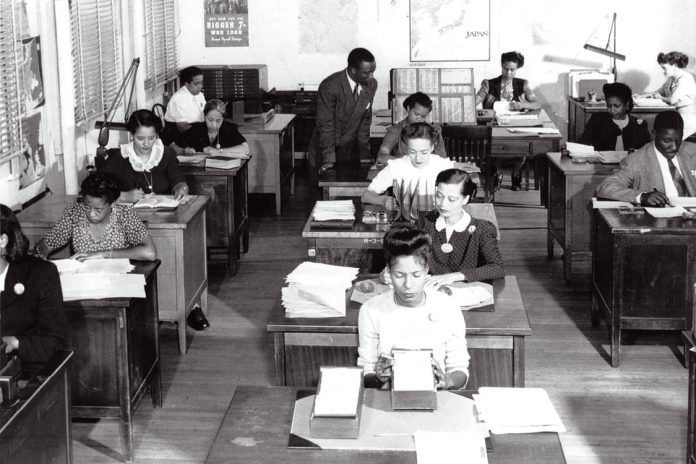

Black “code girls” at Arlington Hall Station. Photo courtesy of Center for Local History, Arlington Public Library

Black “code girls” at Arlington Hall Station. Photo courtesy of Center for Local History, Arlington Public LibrarySheryl Everett Wormley remembers her grandmother Ethel Just as an accomplished scholar and collegiate educator who broke barriers for Black women during the Jim Crow era. With a bachelor’s degree from Ohio State and a master’s from Boston University, Just became dean of women at South Carolina State University around 1950.

Those probably weren’t her only career achievements, although the others are harder to trace. During World War II, a unit of African American women secretly worked as code breakers in Arlington as part of America’s massive intelligence operation, which employed roughly 10,000 women code breakers in total. By deciphering encrypted communications, the women helped the Allied forces target Axis leaders and enemy ships—and even coordinate the D-Day invasion.

Their command center was Arlington Hall Station, a former women’s junior college that became a key wartime cryptography center. (Today it houses the George P. Shultz National Foreign Affairs Training Center at George Mason Drive and Route 50.) The station was unusual for the time in that up to 15% of its workforce was Black—an effort at equity that Eleanor Roosevelt may have dictated herself, according to author Liza Mundy’s book, Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II.

But between the top-secret nature of the work and the racial segregation of the period, even people working at Arlington Hall were unaware that Just’s special unit existed. Whereas stories of their white counterparts have come to light as records have been declassified, the identities of most of Arlington’s Black code breakers remain unknown.

In researching her book, Mundy scoured National Security Agency records, among many other sources, and uncovered only two names of Arlington’s Black women code breakers: Annie Briggs, who headed up the production unit, which worked to identify and decipher codes; and Ethel Just, who led a team of translators.

William Coffee, a Black man, supervised the women and recruited many of them, later winning an award for his wartime leadership.

Genealogical and newspaper archives suggest that the Ethel Just of Arlington Hall was likely Ethel Highwarden Just, a Howard University language professor who married pioneering Black biologist Ernest Everett Just. The couple lived in Washington, D.C., and had three children before they divorced around 1939.

Although definitive proof of Just’s role in the code breaking unit is elusive, the October 1956 edition of The Negro History Bulletin (a periodical launched in 1937 by African American historian Carter G. Woodson) states that Ethel Just worked as a “translator in the War Department.”

Comments

Post a Comment